A Study of the Potential Impacts of LNG Development on Marine Mammals in the Gulf of California

Photo: Breaching humpback whale in the Pacific Ocean

Projected LNG tanker traffic poses serious risks to air quality, underwater soundscape, marine mammals, fragile ecosystems, climate change mitigation, and coastal communities in the Gulf of California.

Context for Research Study

Three liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals are proposed to be developed in the Gulf of California (GoC): Vista Pacifico LNG, American Mexican Integrated Gas Operations “Amigo” LNG Terminal, and Saguaro Energía LNG Terminal (also known as Mexico Pacific LNG). The terminals would import fossil gas from the U.S. via existing and proposed pipelines, liquefy the gas, and then export it to Asian markets using LNG tankers. These projects are backed by supply contracts extending 20 years beyond their startup dates, requiring sustained U.S.–Mexico cooperation through at least 2050—and potentially longer—to fulfill contractual obligations and secure a return on investment.¹,²

Increased tanker traffic could cause significant air and water pollution and underwater noise, threatening the region’s rich marine life, whale habitats, economy, health, and the wellbeing of nearby communities. These projects face growing opposition, including 300,000 signatures gathered by “Whales or Gas”,³ letters to the Mexican Chancellor and the Ministry of the Environment, and a letter from the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC)⁴, all opposing LNG development in the GoC.

To assess the potential environmental impacts of shipping LNG from these three proposed export facilities along the GoC, Equal Routes commissioned a study by Energy and Environmental Research Associates (EERA) and the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur (UABCS), with support from Conexiones Climáticas. The study models how projected increases in LNG tanker traffic could affect regional air quality, underwater noise levels, and marine mammal populations—particularly whales—in the GoC. It also includes an analysis of climate pollutants, such as methane (CH₄) and carbon dioxide (CO₂), that contribute to global warming. The full report is available here.

Gulf of California and Current Shipping Traffic

The GoC hosts federally protected and globally significant marine and terrestrial conservation areas, including a UNESCO World Heritage Site and Important Marine Mammal Areas recognized by the IUCN. Its rich ecosystems support most of Mexico’s marine fisheries catches—representing more than 55% of the national fishing production⁵—and a thriving tourism industry.

Marine ecotourism in the GoC generates 896,000 visits, US$518 million in spending, and 3,575 direct jobs through 256 formal operators each year.⁶

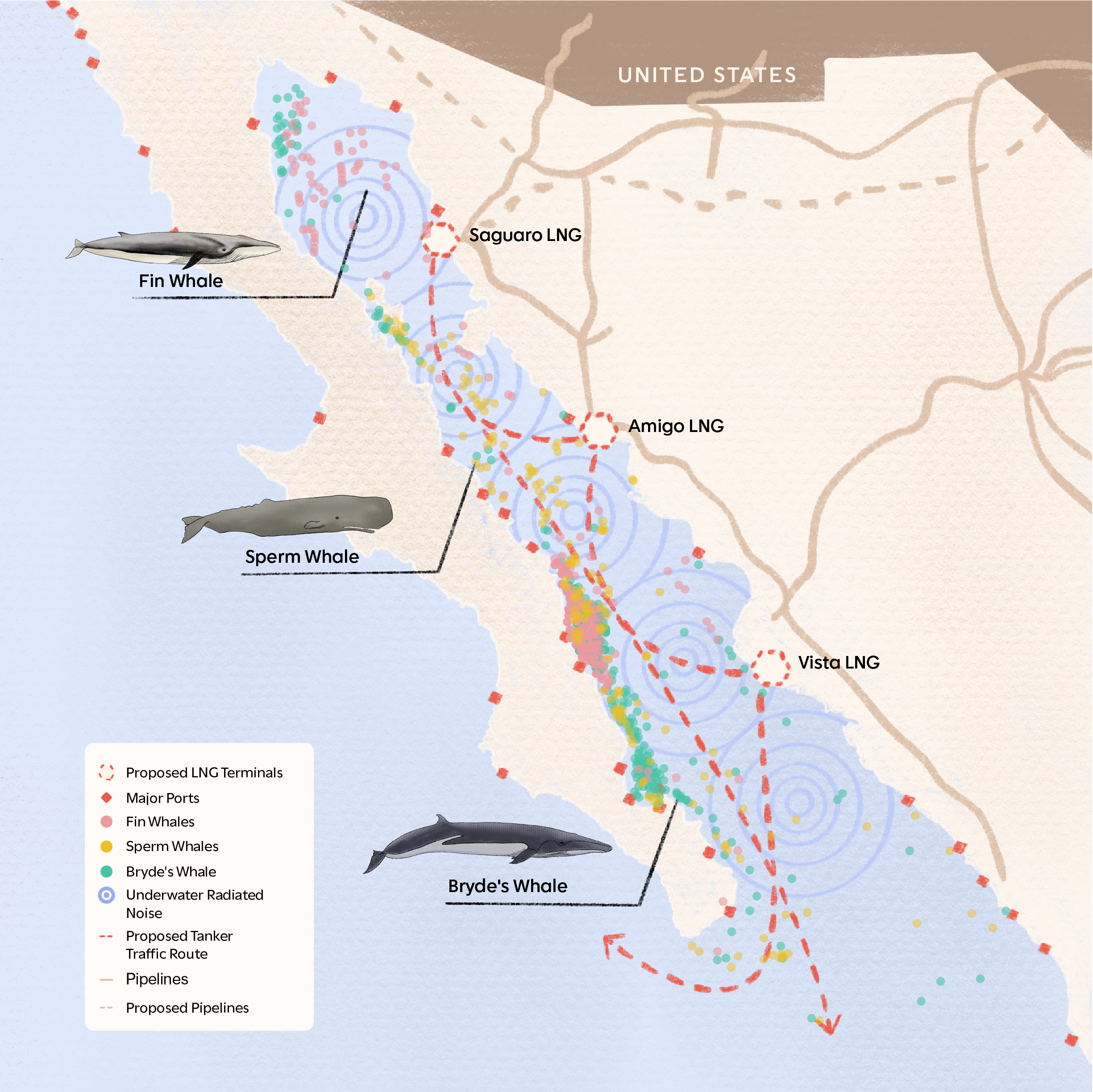

Figure I — Mapping the Overlap: Proposed LNG Infrastructure and Associated Shipping Traffic overlapping with Whale Habitats in the Gulf of California

This map shows the relationship between proposed LNG terminals, proposed shipping routes, and both existing and proposed pipelines, as well as areas of projected underwater noise along the proposed main tanker corridor in the Gulf. These overlapping elements highlight the potential cumulative pressures facing marine mammals in the region, if the proposed LNG projects are approved.

The GoC is often described as a natural laboratory to study biodiversity because it is home to one third of the world’s marine cetacean species and 39% of all marine mammal species globally. It is an essential habitat for a variety of whale species, many of which are highly susceptible to underwater noise. Among the resident whale species are Sperm, Fin, and Bryde’s whales, which have mostly been in the GoC for thousands of years⁷ and spend their entire life cycle within its waters. Migratory species include the Blue and Humpback whales, which are present from November to May, and the Gray whale, found from January through March. These species come to reproduce, give birth, and care for calves. The Fin and the Sperm whales are year-round residents and the world’s most susceptible to ship strikes.

Currently, the GoC experiences relatively low levels of commercial vessel traffic. Shipping activity within the region is largely localized, with higher traffic density concentrated around ongoing ferry routes, cruise ships, and shipments to regional ports such as La Paz, Guaymas, and Topolobampo. Most vessel activity in the GoC consists of small-scale fishing, tourism, and recreational boats. Notably, the limited cargo-carrying vessel traffic that does occur typically remains outside the areas with the highest concentrations of whales.⁸⁹¹⁰

The current anthropogenic threats to whales in the GoC include vessel strikes, entanglements, noise pollution, and broader challenges resulting from habitat degradation and climate change, such as food depletion, marine pollution, and disease.¹¹¹²¹³¹⁴ However, under current conditions, the intensity of these threats is still considered low. For example, known vessel strikes typically involve smaller boats such as pangas (small fishing skiffs), which are not lethal.¹⁵ In contrast, the risk of fatal collisions is higher in areas where larger ships are prevalent.

Risk of LNG Tankers in the GoC

LNG tankers are ships specifically designed to transport and handle large volumes of LNG and are not equipped to carry other types of cargo. Due to their highly flammable and hazardous cargo, these vessels pose inherent safety and environmental risks.¹⁶ Although spills are not often documented, any cargo loss can lead to severe and lasting environmental damage. Methane leaks during transport contribute to continuous cargo loss and require specialized systems to capture or mitigate emissions.¹⁷ The steady release of CH₄ from LNG ships is a known fact that further exacerbates the climate crisis.¹⁸¹⁹

By analyzing LNG tanker traffic patterns at existing U.S. terminals, it is possible to estimate potential activity in the GoC—specifically, the number of expected tanker visits and the resulting increases in emissions and underwater noise. Key factors influencing these impacts include vessel size, speed, and the frequency of calls—each referring to a ship’s arrival at and departure from a port or terminal, typically involving both an inbound and outbound transit.

Increased tanker traffic and whale strikes

On average, the proposed LNG facilities are expected to experience 22.42 vessel calls per million tonnes per year (Mtpa) of export capacity (Table 1). If all proposed Phase 1 of the LNG export terminals in the Gulf of California are built and operate at full capacity, the region could see approximately one call per day. If all three proposed phases are completed, there would be approximately 900 LNG vessel calls per year—or an average of 2.5 tanker arrivals or departures per day.

Proposed LNG exports would introduce new, concentrated traffic bands from large LNG tankers, particularly in the central basin and farther north into the GoC, which currently experience relatively low vessel activity and where several whale species inhabit all year-round (Figure I).

Increased vessel traffic will increase the likelihood of whale strikes in the GoC. Collisions with large vessels can lead to fatal or debilitating injuries in whales, including bone fractures, hemorrhaging, and propeller wounds.²⁰ Vessel strikes are recognized as a significant threat to the survival of large whales.

Increased underwater noise

Noise pollution is a serious threat to marine life, particularly when it is continuous and disrupts the animals’ natural sound environment. High noise levels can cause temporary or permanent hearing loss, and even moderate noise can mask sounds that are important to an animal’s survival, increasing stress and energy use.²¹ Animals may also stop feeding or nursing, struggle to communicate, and/or leave key habitats.²²

Underwater noise is measured in decibels (dB), using a logarithmic scale, where a 10 dB increase represents a 10× increase in sound intensity and a doubling in perceived loudness.²³ Compared to a quiet ocean background level of 90 to 100 dB, a ship generating 174 dB produces a sound roughly 25 to 250 million times more intense, with an acoustic footprint that can extend far beyond the terminal area and its shipping lanes.

In the GoC, source-level noise estimates for LNG tankers are strongly linked to vessel speed, with the loudest underwater noise—up to 192 dB—likely occurring along the main vessel route through the middle of the GoC. This produces low-frequency (deep) sounds that overlap with the noise sensitivity ranges of sensitive whale species, with the potential to impact communication, feeding, and calving behaviours²⁴ (Figure V).

Increased emissions and air pollutants

Vessel-sourced emissions include greenhouse gases like CO₂ and CH₄, as well as air pollutants such as nitrogen oxides (NOₓ) and particulate matter (PM₁₀ and PM₂.₅), which can harm human health and the environment. CO₂ and CH₄ contribute to climate change by trapping heat in the atmosphere. CH₄ and NOₓ contribute to ground-level ozone and smog, while particulate matter consists of black carbon (also contributing to climate change) and tiny particles that can penetrate deep into the lungs and bloodstream. All can cause or worsen respiratory issues, lung cancer, heart disease, cancer, and strokes.²⁵²⁶

Marine engines face a tradeoff between CH₄ and NOₓ emissions, where optimizing the engine to reduce one can increase the other. Engines are typically optimized to reduce NOₓ because of international, national, and port regulations due to concerns over the health impacts on coastal communities. Optimization to address NOₓ means that CH₄ emissions may be higher.

CH₄ emissions originate from the LNG tanker’s engine and cargo storage. Most LNG tankers are equipped with low-pressure dual-fuel (LPDF) two- or four-stroke engines, which can operate on either diesel or LNG. These engines are known to emit high levels of unburned methane—referred to as methane slip. Another source of emissions is boil-off gas (BOG), which results from LNG vaporizing due to heat exposure during storage or transport.

The projected emissions from LNG tankers at the proposed Mexican export facilities in the GoC will increase relative to terminal capacity (Table II).

The emissions from a single round-trip voyage to a proposed LNG facility are equivalent to the annual emissions of approximately 48–166 gasoline-powered passenger vehicles, with facilities located farther into the GoC generating substantially higher GHGs per voyage.

If all three proposed terminals were operating at full capacity, the total annual emissions from LNG tanker traffic would be equivalent to the yearly emissions of nearly 130,000 passenger vehicles or more than 60 million gallons of gasoline consumed.²⁷ These estimates represent only the localized emissions within the GoC shipping lanes.

Other environmental risks beyond the study scope

While not explored in the report, the following risks are recognized as relevant considerations and warrant further investigation in future assessments. Increased vessel traffic in the GoC can introduce other severe environmental impacts.

For example, ships discharge different types of wastewater—including ballast water (used to balance the ship), greywater (from sinks and showers), blackwater (sewage), and bilge water (a mix of oil, fuel, and water from the bottom of the ship). These discharges can pollute the ocean and spread harmful bacteria, chemicals, microplastics, or invasive species that disrupt local ecosystems.

Other concerns include the buildup of organisms on ship hulls (called biofouling), which can also spread invasive species to new areas, and the use of anchors in open water, which can damage fragile habitats like coral reefs and seagrass beds.

Additional impacts from building the proposed LNG terminals and long-term operations on land may include dredging and port expansion, increased light pollution, and emissions from the fossil gas supply chain.

Locking in transboundary fossil fuel dependency

LNG export development in the GoC risks deepening transboundary extractive dependency. The planned LNG terminals require sustained fossil gas supplies to be financially viable—gas that would primarily come from expanded fossil gas extraction in the U.S., transported via cross-border pipelines. Within Mexico, long-term gas agreements—some lasting up to 30 years and signed during the Peña Nieto administration era (2012–2018)—combined with rising national energy demand, are further entrenching the country’s reliance on U.S. gas. The proposed LNG terminals are already tied to upstream infrastructure expansion, effectively locking Mexico into a fossil fuel trajectory that extends well beyond the marine region.

Conclusion and recommendation

The proposed LNG terminals—and the resulting increase in LNG tanker traffic—pose serious threats to the GoC’s unique biodiversity and conservation areas, including those designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and Important Marine Mammal Areas.

These developments increase the risks of air, water, and underwater noise pollution. Given the GoC’s critical ecological role—particularly as a habitat for resident and migratory marine megafauna—a precautionary approach to industrial development is essential.

It is increasingly evident that the region’s ecological integrity is incompatible with the scale and nature of heavy marine traffic associated with proposed LNG facilities. These projects directly conflict with the environmental and community values of the GoC. In light of the risks and potential impacts, the burden of proof must rest with project proponents to demonstrate otherwise.